|

Civil War Battles |

|

State War Records |

| AL - AK - AZ - AR - CA - CO - CT - DE - FL - GA - HI - ID - IL - IN - IA - KS - KY - LA - MA - MD - ME - MI - MN - MS - MO - MT - NE - NV - NH - NJ - NM - NY - NC - ND - OH - OK - OR - PA - RI - SC - SD - TN - TX - UT - VT - VA - WA - WV - WI - WY |

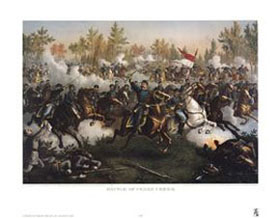

The Battle of Cedar Creek

October 19, 1864 in Frederick,Shenandoah, and Warren Counties, Virginia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

After twice beating Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s army, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan had switched to destroying the resources of the Valley so that no Confederate army could again support itself there and no foodstuffs would move east to Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army. He also withdrew slightly closer to his supply lines and prepared to detach one of his 3 veteran infantry corps. But Early was reinforced and urged to be aggressive – and from Lee a letter urging something was usually more effective than a direct order from other generals.

Early examined the Union position behind Cedar Creek and found an opening. Expecting an attack across the open valley floor to the west, the Union left relied on natural obstacles for cover. Early reckoned he could get his men across the Creek and pounce on the Union left, then roll up the line defeating each part in sequence. A bright moon helped the night marches (Early deployed his men in 3 columns, a risky move that only experienced commanders with reliable staff officers could safely try) and at dawn everyone was in place.

At dawn, October 19, the Confederate Army of the Valley under Early surprised the Union army at Cedar Creek and routed the VIII and XIX Army Corps. The surprise was complete, and the first Union corps (Crook’s VIII) fought momentarily, then broke. Hundreds of prisoners were taken. The XIX Corps (Emory) soon melted too. The Confederates were too quickly through Crook’s men for Emory’s to brace themselves; they also had to deploy facing south rather than west across the Creek – meanwhile Confederate guns across the Creek shelled the open Union flank. Wright’s VI Corps was the last hope for the Federals, and it fought a stout defensive battle, giving ground to be sure, but retaining its cohesion and covering the wreckage of four other infantry divisions.

Early was well pleased with his victory, as his men gathered well over a thousand prisoners, eighteen guns, and much other booty. Actually Early was too pleased, and didn’t press his advantage. He assumed Wright’s men would acknowledge defeat and withdraw, leaving the Confederates holding the field and all the fruits of victory. Exactly the opposite happened. Sheridan was back at Winchester after being called to a conference in Washington, and heard the booming of the guns. Once he could tell it was a real battle rather than a skirmish, he put spurs to his horse and pounded down the Valley Pike.

Maj. General Philip Sheridan arrived from Winchester to rally his troops, and, in the afternoon, launched a crushing counterattack, which recovered the battlefield. The afternoon attack had driven the Confederates from the field even faster than the Confederate morning attack had swept the Federals back, mainly because Confederate morale snapped. Early’s men had won a substantial victory but Earlyl had sat still; then the Union troops realized they still had a strong chance. Sheridan held his nerve when Early was too cautious, and the troops could sense the difference and responded.

The Union victory broke the back of the Confederate effort in the Shenandoah.

Not only had they lost 3 straight battles, they’d lost artillery and supplies, so the infantry that remained were weaker than their numbers suggested. And the Confederate force was divided amongst itself: there was plenty of blame but nobody wanted to share. The Shenandoah was sealed off to the Confederates, not only by Sheridan’s army but because of the wrecked farms. Meanwhile, Sheridan could go ahead and send Wright’s veterans to Petersburg and settle down the rest for the winter. What’s more, the string of victories helped Pres. Lincoln along to victory in his November battle with George B. McClellan.