|

Civil War Battles |

|

State War Records |

| AL - AK - AZ - AR - CA - CO - CT - DE - FL - GA - HI - ID - IL - IN - IA - KS - KY - LA - MA - MD - ME - MI - MN - MS - MO - MT - NE - NV - NH - NJ - NM - NY - NC - ND - OH - OK - OR - PA - RI - SC - SD - TN - TX - UT - VT - VA - WA - WV - WI - WY |

The Battle of Chickamauga

September 18-20, 1863 in Chickamauga, Georgia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chattanooga was an important for its key railroad junction. If the Union army could possess Chattanooga, it could allow its armies to strike south towards Atlanta and the Carolinas. It would also allow them to threaten Richmond, Virginia as a passage through southeast Virginia. The Confederate Army wanted to keep Chattanooga in its possession so it could continue to threaten eastern Tennessee and Kentucky with an invasion platform.

After the Battle of Murfreesboro, both Gen. William S. Rosecrans, with his Army of the Cumberland, and Gen. Braxton Bragg, with his Army of Tennessee, had stayed around the same general area during the winter months. In June, Rosecrans began to move his army towards Chattanooga with the purpose of pushing Bragg and his army out of the city. Rosecrans headed into north Alabama and swung across to north Georgia and back into Tennessee, approaching Chattanooga from the rear.

On September 9, Bragg had found out that Rosecrans was approaching Chattanooga from the rear and decided that it would be better to abandon the city instead of being caught in a siege. Gen. Later in the day, Rosecrans had occupyed Chattanooga. Bragg retreated 20 miles south to Lafayette, Georgia. He planned on attacking the Union army when they moved out so that he could go back and reoccupy Chattanooga.

There was not any other major fighting in the area, so Bragg was able to get plenty of reinforcements from the surrounding Confederate armies. Bragg got the troops that he had previously sent to Vicksburg, Mississippi, a corps from Knoxville, and 15,000 men from the I Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. This made his army almost 72,000 men strong.

Knowing that Rosecrans would be travelling in his direction, Bragg started to spread rumors that his army was demoralized and that it was falling apart. When Rosecrans heard these reports, he believed them. Now knowing this, he moved his army, about 57,000 men, in 3 seperate columns, with each column 20 miles apart from each other. Moving through mountainous terrain, this meant that the columns would not be able to help one another if one of them were to be attacked. Rosecrans did not expect any trouble, so he felt safe with this movement plan.

When Bragg found out this information, he made his plan of attack. He would attack the left Union column first, and then move on to the next one. He assumed that there was only 2 columns intstead of 3 columns. In all actuality, he would be attacking the middle column and he would move out before all of Longstreet's men would arrive.

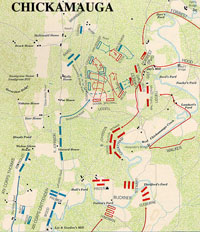

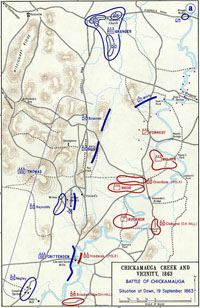

On September 18, Bragg planned to strike the Union left column and push them southwest into the mountains. This would open up the way to Chattanooga for Bragg. He would actually attack the Union center corps, thus losing the element of surprise. His corps commanders did not heavily engage Rosecrans. All that was accomplished was that Rosecrans discovered that Bragg's army was not demoralized and in disarray. Rosecrans decided to concentrate his army so that Bragg could not cut off and attack his corps individually.

Bragg wanted to cross the Chickamauga Creek, but found out that the crossing were guarded by Union troops. That night, Bragg's army had finally crossed the creek at different places. Nearly 2/3 of his army had crossed the creek, and held the fords at Lee's Mill and Gordon's Mill. Rosecrans realized what Bragg was doing and sent Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas's corps to secure the army's left flank.

On September 19, the Union line was stretched for 6 miles across. The Confederate right wing was commanded by Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk , and the left wing was commanded by Longstreet. The battle had been begun by Croxton's brigade of Brannan's division, which struggled sharply with Maj. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest's Confederate cavalry.

The battle raged back and forth until dark. Both Rosecrans and Bragg had sent their armies into battle by piecemeal instead of a large, strong push. The Confederates dashed through the lines of the Federals and captured an artillery battery and about 500 Federals. In the charge, all of the horses and most of the men of the batteries were killed. At that moment, a heavy Union force came up and joined in the battle.

They now outnumbered and outflanked the Confederates, and, attacking them furiously, drove them back in disorder for a mile and a half on their reserves. The lost battery was recovered, and Brannan and Baird were enabled to reform their shattered columns. There was a lull, but at 5:00 P.M., the Confederates renewed the battle, and were pressing the Union line heavily, when Hazen, who was in charge of a park of artillery—20 guns—hastened to put them in position, with such infantry supports as he could gather, and brought them to bear upon the Confederates, at short range, as they dashed into the road in pursuit of the Federals. The pursuers recoiled in disorder, and thereby the day was saved on the left.

There had been some heavy artillery fighting on the Union right during the day. At 3:00 P.M., Maj. Gen. John B. Hood sent 2 of his divisions against Brig. Gen. Jefferson Davis's division, pushing it back and capturing an artillery battery. Davis fought until near sunset, when a brigade of Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan's division came to his aid. Then a successful Union counterattack was made against the Confederates. The Confederates were driven back, the battery was retaken, and a number of Confederates prisoners were taken.

That night, preparations were made by both army commanders for the next morning's battle. Rosecrans had his men pull back to better a defensive line in the woods.

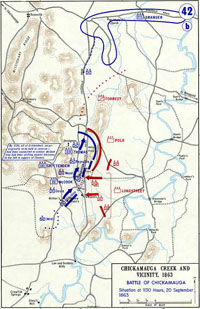

On September 20, Polk was supposed to start his attack on the Union left flank at 6:00 A.M. When Bragg did not hear any fighting by 9:00 A.M., he went to look for Polk. He found Polk some 3 miles behind the Confederate line reading a newspaper and waiting for breakfast. Meanwhile, under cover of the fog, Thomas received reinforcements until nearly half of the Army of the Cumberland present were with him. They began to erect breastworks and piling up debris to create obstacles for the Confederate attackers.

The Confederates hit Thomas' line and made it curl back. While Thomas managed to hold, he requested some reinforcements from Rosecrans. While the Union center and right flank was not engaged in battle, Rosecrans shifted troops from there to Thomas. Rosecrans was inspecting his lines when there appeared to be a gap in the center of his lines, although there was a division in the thick woods forward of where Rosecrans could not see. He ordered Brig. Gen. ?? Wood to fill in the gap in the center. Woods, who had been a victim of Rosecrans violet temper tantrums earlier for not following orders, complied with Rosecrans orders without questioning whether such orders made sense. When Woods moved, this created a 1/4 mile gap in the line.

At the precise time the gap was created, Longstreet was initiating his attack. He charged through the opening, into the open flank, and nearly a mile into the rear of the Union army. With this charge, the Union right flank was shattered and began crumbling. They soon began fleeing in disorder towards Chattanooga. Rosecrans and most of his staff had been standing at the gap when Longstreet came through. The retreating Federals had swept Rosecrans and his staff up in the running mob. Before he knew it, he was in Chattanooga and was unable to return to the battlefield. For all he knew, the entire Union army had been wrecked.

Thomas saved the Union army from complete disaster. His left flank had formed a horseshoe when Polk's wing had pushed the Union line backwards. Thomas formed the line on the only prominent piece of terrain on the battlefield, Snodgrass Hill. Thomas stood with the remnant of 7 divisions. He gathered the units, formed them up, and sent them to the defensive line. He would earn the name "Rock of Chickamauga."

Longstreet was in charge and was sending attacks against Thomas, hoping to break his defensive position. Bragg did not use Polk in any of the attacks against Thomas. This would cause the Confederates from destroying the Union force on the hill. Bragg also did not pursue Thomas when he retreated to Chattanooga. Brig. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest, Bragg's cavalry commander, watched while the Union army was moving to Chattanooga. He urged Bragg to chase them and drive them into a wedge between Rosecrans and Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. This would force them to retreat and leave Chattanooga in Confederate hands again. Bragg did not think that he had won the battle and therefore would not pursue the Federals. Forrest was infuriated with Bragg and refused to serve under him anymore.

Without much hope, Thomas and his men repulsed several Confederate assaults until the sun went down. After ammunition was running low, he began withdrawing his troops to Rossville.

At Rossville, Thomas had the first reliable information of disaster on the right. Confederates seeking to obstruct the movement were driven back. In the evening, the entire Union army withdrew to a position in front of Chattanooga. The Battle of Chickamauga had come to an end.

On September 21, Bragg advanced and took possession of Lookout Mountain, Lookout Valley, and all of Missionary Ridge. He would put Chattanooga under a siege. See the Battles of Chattanooga: Orchard Knob, Lookout Mountain, and Missionary Ridge for more information.