|

Civil War Battles |

|

State War Records |

| AL - AK - AZ - AR - CA - CO - CT - DE - FL - GA - HI - ID - IL - IN - IA - KS - KY - LA - MA - MD - ME - MI - MN - MS - MO - MT - NE - NV - NH - NJ - NM - NY - NC - ND - OH - OK - OR - PA - RI - SC - SD - TN - TX - UT - VT - VA - WA - WV - WI - WY |

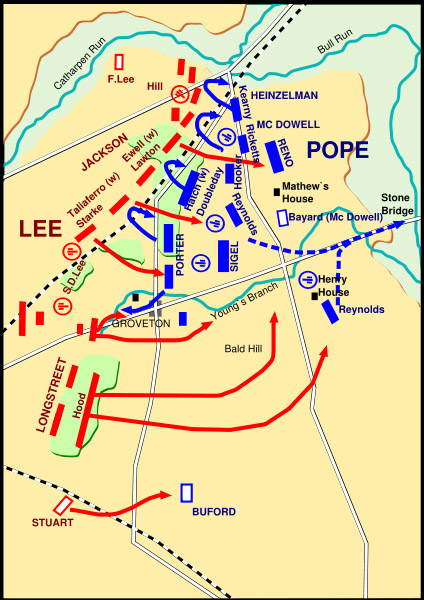

The Battle of Manassas/Bull Run (Second)

August 28-30, 1862 in Manassas, Virginia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

During late June and early July 1862, Gen. Robert E. Lee's army was able to break a Union stranglehold on the Confederate capital at Richmond, and drive Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac back into the Virginia Peninsula. Having lost the initiative, McClellan disembarked his army on naval transports back to Washington, D.C . In the meantime, Lee undertook a campaign against Pope's Army of Virginia, which was ominously perched along the Rapidan River. If Pope's army were allowed to link up with McClellan's, their combined force would exceed 180,000 men—far too many for Lee to defeat with his army of 60,000 men.

On August 9, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. " Stonewall" Jackson narrowly defeated Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, opening the series of tactical maneuvers that would culminate in the confrontation near Bull Run. After this engagement, Lee sent 30,000 men under Maj. Gen. James Longstreet to reinforce Jackson and soon arrived himself to assume command of the combined force. A cavalry raid on Pope's headquarters at Catlett Station on the night of August 22–23 yielded his tent, dress coat, $350,000 in cash, and his dispatch book.

In the details of the dispatch book, Lee's fears were confirmed: elements of McClellan's army were seeking to link up with Pope's. The Confederate general immediately sought to defeat the Army of Virginia before it could be reinforced.

On August 25, he sent Jackson and 24,000 men on a wide flanking movement around Pope's right. While the Union commander remained oblivious at the Rappahannock River, Jackson's men poured through Thoroughfare Gap and captured a significant store of Federal supplies at Manassas Junction. The food and clothing they obtained provided a welcome reward for their 36-hour forced march. The Confederates then burned what they could not take.

On August 27, Pope realized his untenable position and moved to intercept Jackson from the southwest, while General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck directed Federal forces in Alexandria to move against Manassas Junction and Gainesville from the east. Meanwhile, at Bristoe Station, Jackson's rearguard under Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell held off Pope's advance forces under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. With Pope's army approaching from the west, Jackson decided to withdraw his command during the night to a railroad bed running roughly parallel to the Warrenton Turnpike, then curving off to the north as it ran eastward.

On August 28, the engagement began as a Union column, under Jackson's observation near Brawner Farm, moved along the Warrenton Turnpike. In an effort to prevent Pope from moving into a strong defensive position around Centreville, Jackson risked being overwhelmed before Longstreet could join him. Jackson ordered an attack on the exposed left flank of the column and, in his words, "The conflict here was fierce and sanguinary." The fighting continued until approximately 9:00 P.M., at which point the Union withdrew from the field. Losses were heavy on both sides.

Pope believed he had "bagged" Jackson and sought to capture him before he could be reinforced by Longstreet. Jackson had initiated the battle with the intent of holding Pope until Longstreet arrived with the remainder of the Army of Northern Virginia. The next day would test if his men were able to hold their positions in the face of a numerically superior enemy, long enough to be reinforced.

On August 29, Pope launched a series of assaults against Jackson's position along an unfinished railroad grade, but he never managed to coordinate the attacks. As a result, the outnumbered Confederates managed always to survive the repeated blows. The attacks were repulsed with heavy casualties on both sides. The left, under Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill, quivered under severe attack, but Jackson calmly expected they would hold and somehow the Light Division managed. It was a close run thing: one Confederate unit ran out of ammunition and had to throw rocks; if they’d done the ‘sensible’ thing and retreated, or if the Union troops had just a little more pluck to plunge in with the bayonet, Jackson’s line surely would have snapped.

Twice the line was broken, once by Hooker’s division and once by Maj. Gen. Phil Kearny. Both times the Confederates counterattacked, and Pope didn’t have enough men up to support, and Jackson’s line held. At the end of the day, Jackson pulled his main body back to rest, leaving only pickets along the railway line. Pope, optimistic to the last, thought he’d won, that Jackson had left a rearguard to cover a retreat. During the day, Longstreet’s larger ‘wing’ arrived and took positions on Jackson’s left, but didn’t enter action, even though the Union flank was open. Longstreet was a cautious man, Jackson was holding his own, Lee didn’t like throwing troops in piecemeal, and there were Union columns in a position to smash Longstreet’s flank if he attacked. So he deployed quietly, almost unnoticed.

On August 30, Pope renewed his attacks, seemingly unaware that Longstreet was on the field. Pope took his time organizing what he thought was going to be a pursuit. He intended to smash Jackson’s ‘rearguard’ and steamroller whatever he could catch. He gathered his forces and formed three strong lines. Jackson slid his men back into their defensive positions, but it was obvious that he’d be overrun if he didn’t get some help. He asked Lee to have Longstreet chip in, and ‘Old Pete’ was happy to help. Union troops were no longer moving across his front, and all his subordinates were in position, so he moved. Before his infantry could move out and catch the Union flank, Lee’s artillery battalion, posted between the two Corps, opened up. Their shells slammed into the Union flank.

The 2nd and 3rd lines hesitated, stopped, fell back. Longstreet's wing of 28,000 men counterattacked in the largest, simultaneous mass assault of the war. Without support, the first line looked at Jackson’s men ahead of them and Longstreet’s to the flank and knew better than to continue the attack.

Expecting a pursuit against a beaten foe, the last thing the Union troops wanted was another stand-up fight. The Union left flank was crushed and the army driven back to Bull Run. Only isolated resistance an effective Union rearguard, a few brigades that held their nerve, including Kearny, prevented a replay of the First Battle of Manassas/Bull Run disaster. No matter how sturdy the rearguard, most Union soldiers had had enough: the retreat to Centreville was precipitous.

On August 31, Lee ordered a pursuit. The Union left flank was crushed and the army driven back to Bull Run. Only an effective Union rearguard action prevented a replay of the First Manassas disaster. This was the decisive battle of the Northern Virginia Campaign.

After a very indecisive but bloody Peninsular Campaign and one year after the First Battle of Bull Run, President Abraham Lincoln and his advisers felt that it was time to try a new general in place of McClellan. They agreed on John Pope , who had been fairly successful in the west. Second, the Cabinet decided that the following major forces in the North should come together: the Armies of the Valley (united under Pope); Burnside (ordered north from Fortress Monroe to Falmouth); and McClellan was directed to bring his great army to Alexandria and unite with Pope.

There was one major flaw in the Union's complex maneuvers. They had forgotten that Lee's Army of Virginia was located between all of them. Being an excellent general, Lee seized the moment to attack the individual armies before they converged to beat an almost unbeatable force. After a sharp fight at Cedar Mountain near Culpeper Court House, Jackson swung around to attack a supply depots and Pope's headquarters at Manassas Junction on August 26. At the time Pope was trying gather his army at Rapidian.

Quickly, Pope turned to try and corner Jackson and he thought he had him but Jackson marched west to Groveton and invited Pope's attack. With Jackson's soldiers used to the long marches they had no trouble holding off Pope's following army near Groveton. As the fighting was occurring near Groveton, Longstreet was hurrying up the valley between the Blue Ridge and the Bull Run Mountains. On August 29, he turned up east, forced Thoroughfare Gap-Which pope had left practically undefended-and the next day struck Pope's left flank, defeated it, and sent the whole army reeling toward Bull Run.

Unable to escape blame for this debacle, Pope was relieved of command. On the contrary, the hopes of the Confederacy were gleaming brighter than ever. Within one week, the vanguard of the Army of Northern Virginia would cross the Potomac River in the Maryland Campaign, marching toward a fateful encounter with the Army of the Potomac at a creek called Antietam.

The battle ended in a cloud of confusion and doubts about just how loyal the Union army was to each other. Porter's corps had stood idle the whole afternoon of August 29. Banks's 6,500 men had not taken any part in the fight; McClellan had failed to get any part of his large army to Pope in time to do any good. Porter was later made the scapegoat for all this tragedy of errors, but the real failure was Pope's and McClellan's.

Lee's tactical scheme to halt McClellan's advance towards Richmond, Jackson's stalwart defense, and Longstreet's timely attack resulted in a complete Confederate victory, and Pope was justifiably discredited as a general. He blamed the officers of the Army of the Potomac for conspiring against him, but he saw Confederates where they were not and refused to see them where they were. The Confederate victory at the Second Battle of Manassas/Bull Run cleared the way for an invasion of the North.