|

Civil War Battles |

|

State War Records |

| AL - AK - AZ - AR - CA - CO - CT - DE - FL - GA - HI - ID - IL - IN - IA - KS - KY - LA - MA - MD - ME - MI - MN - MS - MO - MT - NE - NV - NH - NJ - NM - NY - NC - ND - OH - OK - OR - PA - RI - SC - SD - TN - TX - UT - VT - VA - WA - WV - WI - WY |

The Battle of Pea Ridge

March 6-8, 1862 in Benton County, Arkansas

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Battle of Pea Ridge was also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern. The outcome of the battle essentially cemented Union control of Missouri.

The Confederates were eager to return to Missouri. Meanwhile, President Abraham Lincoln wanted to hold as many "Border States" in the Union as possible. The Confederate victory at the Battle of Wilson's Creek in the summer of 1861 had favored the Confederacy, but when Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis was appointed, he restored Union fortunes. Reinforced, and more active than his predecessor Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont, he'd not only secured Missouri, he'd pushed down into northwest Arkansas.

Union forces in Missouri, during the latter part of 1861 and early 1862, had effectively pushed Confederate forces out of the state. By the spring of 1862, Curtis determined to pursue the Confederates back into Arkansas with his Army of the Southwest. He moved his force and 50 artillery pieces into Benton County, along a small stream called Sugar Creek. Union forces consisted primarily of soldiers from Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Ohio. Over half of the Union soldiers were German immigrants. Curtis found an excellent defensive position on the north side of the creek and proceeded to fortify it and place artillery for an expected Confederate assault from the south.

Brig. Gen. Sterling Price and Brig. Gen. Ben McCulloch had proved disappointments the previous year, and there was a further reason not to promote either one: they detested each other, and if one was promoted some of the other's men would desert. So President Jefferson Davis dipped into his limited stock of diplomacy and in the early spring of 1862 appointed a new commander: Van Dorn. Van Dorn worked hard on his new command in the few days he allowed himself. He had been appointed overall commander of the Trans-Mississippi District to quell a simmering conflict between Price and McCulloch. Van Dorn's Army of the West totalled approximately 16,000 men, including 800 Cherokee Indian troops, Price's Missouri State Guard, Texas Rangers, and Confederate infantry from Arkansas and Louisiana.

Van Dorn was aware of the Union movements into Arkansas and was eager to attck and destroy Curtis's Army of the Southwest and reopening the gateway into Missouri. Van Dorn rode for 2 days to join his command, catching a fever in the wintry valleys of northern Arkansas. His plan was relatively simple: advance soon, while the Union forces were scattered in winter quarters, win whatever battles were necessary and create momentum that would take him "Huzza for St. Louis".

On March 4, he split his army into 2 divisions under Price and McCulloch and ordered them to march north along the Bentonville Detour with the hopes of getting behind Curtis and cutting off his lines of communication. Van Dorn left his supply trains behind in order to make better speed, a decision that would later prove to be a crucial one. The Confederates made an arduous 3 day forced march down the Bentonville Cutoff from Fayetteville in the midst of a freezing storm. Many of the Confederate soldiers were ill-equipped and barefoot.

The first step was to win the first battle, and it would be hard, despite his 3-to-2 numerical advantage over Ryan's 10,000 men. Van Dorn faced a difficult task: he had to attack a competent enemy in constricting terrain, where the Confederate's superiority in numbers would matter less. To make things worse, Ryan had picked a strong position, on a small ridge overlooking a stream with marshy flanks. Van Dorn took a look at it and knew no frontal attack could succeed.

So he revised the plan, now intending to outflank the Federals and fall on their unprotected rear by a 2-pronged night march. He would win the battle thanks to numbers and surprise, then Ryan would have nowhere to retreat and Van Dorn would capture the Union remnants.

The Confederates arrived at their destination strung out along the road, hungry and tired. The late arrival of McCulloch compounded the Confederate problem, which led Van Dorn to split his forces in two. Van Dorn ordered McCulloch to circle around the western end of Pea Ridge, turn east along the south face and meet Price's division at Elkhorn Tavern. Van Dorn and Price would travel east along the north face of the ridge, secure Elkhorn Tavern, and wait for McCulloch.

These Confederate delays allowed Curtis to begin repositioning his army to meet the unexpected attack from his rear and get his forces between the two wings of Van Dorn's forces.

McCulloch's force consisted of Confederate troops under Gen. James McIntosh and 2 divisions of Cherokee Indians under Brig. Gen. Albert Pike.

Van Dorn left campfires burning and deceived Ryan about the Confederate plan. The night march got a bit chaotic, and some units didn't turn up where they were intended, and even more were late, which gave Curtis time to redeploy a bit.

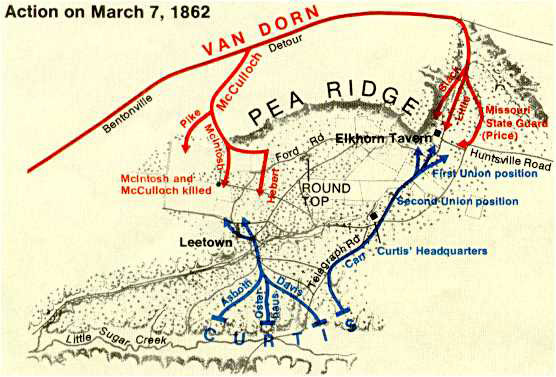

On March 6, on the other side of Pea Ridge, Van Dorn and Price encountered the Federals near Elkhorn Tavern. Van Dorn ordered an attack and by nightfall, the Confederates succeeded in pushing the Union forces back. They seized the Telegraph and Huntsville Roads and succeeded in cutting Curtis's lines of communication at Elkhorn Tavern. The survivors from McCulloch's command joined Van Dorn at Elkhorn Tavern during the night.

On March 7, McCulloch's troops swung westward around Pea Ridge and plowed into elements of the Union army at a small village named Leetown, where a fierce firefight erupted. Curtis held the smaller Confederate force with McCulloch's men coming from the west with a cavalry screen. It didn't last long, and a combined Cherokee-cavalry charge routed the Union cavalry. McCulloch couldn't maintain the momentum, and by the time he could again move his men forward, the Federals had a defensive line. McCulloch was killed leading a charge and McIntosh was also killed in action soon after the attack began. Then, Col. Louis Hébert was captured. These events effectively shattered the Confederate command structure and they were unable to organize an effective attack in the resulting chaos. McCulloch's second-in-command fell soon after, and the third-in-command was captured. The Confederates didn't know who would take over, and Pike, the eventual choice, inspired few. This part of the battle ebbed to an end, neither side able to take advantage of the other's fatigue and confusion.

The main Confederate force, with Price and the sick Van Dorn ran into stronger Union forces, under Col. Eugene Carr. The Confederates used their artillery well, and pushed Carr back through successive defensive lines, but never took many prisoners: the Union troops kept their cohesion and kept on fighting. It was an ominous sign for the tired, ill-supplied Confederates and as the late-winter sun sank the battered Union line was still intact near the Elkhorn Tavern.

Van Dorn hoped that Ryan's men were damaged and discouraged enough that they'd surrender. But if they didn't van Dorn was the one in trouble: his men were tired, short of food and ammunition. Worse, the forces were separated, the 2 Confederate columns had the Union army in between. Ryan didn't budge, and when the dawn came his men were still in the middle of the 2 Confederate forces. Ryan had also brought up his reserve, the 2 fresh divisions of Sigel's force.

Pike's men stayed quiet, tying down some Union forces to the west of Elkhorn Tavern. The tables on the northern flank were turned: Ryan had more and better artillery, with plenty of ammunition. He had more infantry, and morale was high. Van Dorn staked all he had left on an impressive opening show, and he began bombarding the Union lines. But his guns were soon smothered by the superior Union artillery, which first battered the Confederate guns, then turned on the Confederate infantry. Once the guns had prepared the way, Sigel's men charged, and the Confederate lines broke. Carr's and Davis' divisions joined the advance, and Van Dorn's army melted away. There were more deserters rather than battle casualties. Still, they would not be fighting for the Confederate army and that was what mattered.

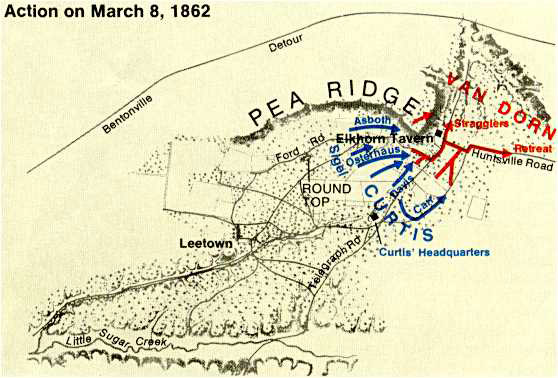

On March 8, in the morning, Curtis massed his artillery near the tavern and launched a counterattack in an attempt to recover his supply lines. Leading the attack was Curtis's second-in-command, Franz Sigel. The massed artillery combined with cavalry and infantry attacks began to crumple the Confederate lines. By noon Van Dorn realized that he was low on ammunition and that his supply trains were miles away with no hope of arriving in time to resupply his men. Despite outnumbering his opponent, Van Dorn had no choice but to withdraw down the Huntsville Road.

With the defeat at Pea Ridge, the Confederates never again seriously threatened the state of Missouri. Within weeks Van Dorn's army would be transferred across the Mississippi River to bolster the Army of Tennessee, leaving Arkansas virtually defenseless.

With his victory, Curtis proceeded to move farther into undefended Arkansas with the hope of capturing Little Rock.

The Confederates had to abandon plans to invade Missouri. Instead, Ryan was secure in northern Arkansas, while the Confederate forces were dispersed to regions more immediately threatened. Price wouldn't return to Missouri until mid-1864, by when it was too late.

|

|