|

Civil War Battles |

|

State War Records |

| AL - AK - AZ - AR - CA - CO - CT - DE - FL - GA - HI - ID - IL - IN - IA - KS - KY - LA - MA - MD - ME - MI - MN - MS - MO - MT - NE - NV - NH - NJ - NM - NY - NC - ND - OH - OK - OR - PA - RI - SC - SD - TN - TX - UT - VT - VA - WA - WV - WI - WY |

The Battle of Manassas/Bull Run (First)

July 21, 1861 in Manassas, Virginia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Books on The Battle of Manassas / Bull Run & the 1st Manassas/Bull Run Campaign

are available from Amazon.com

By early summer of 1861, the war-fevered citizenry of the Union and the newly established Confederacy were clamoring for the fighting to begin. Pressured by public opinion, opposing presidents Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln urged their respective armies to begin offensive operations.

Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell was appointed by President Abraham Lincoln to command of the Army of Northeastern Virginia. Once in this capacity, McDowell was harassed by impatient politicians and citizens in Washington, D.C. who wished to see a quick battlefield victory over the Confederates in northern Virginia. McDowell, however, was concerned about the untried nature of his army. He was reassured by Lincoln, who responded, "You are green, it is true, but they are green also; you are all green alike." Against his better judgment, McDowell started his campaign.

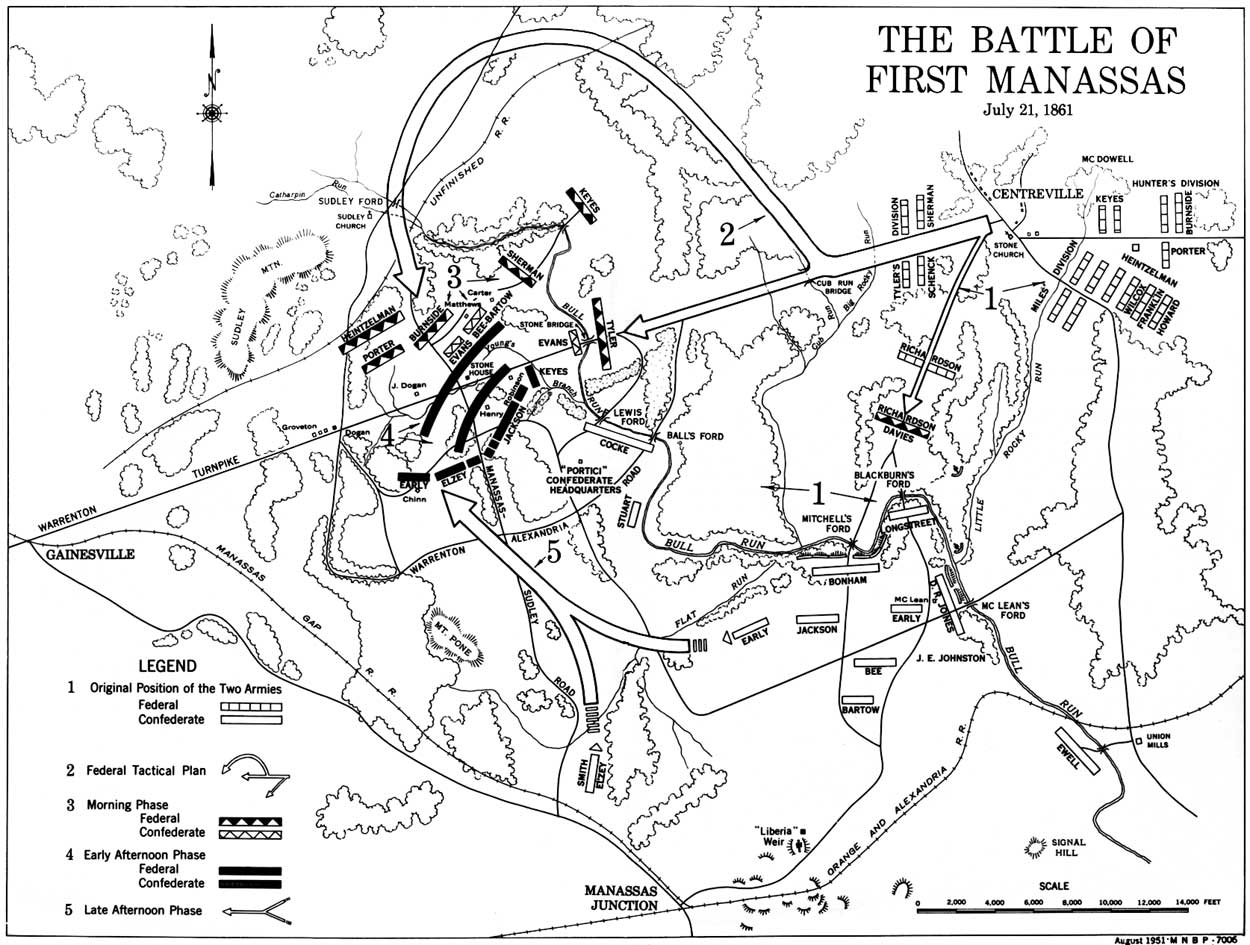

On July 16, Lincoln ordered McDowell to leave Washington, D.C. and attack the Confederate forces, commanded by Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, and drive them from Manassas Junction. Manassas Junction was a vital railroad center about 29 miles southwest of Washington, D.C. McDowell planned to swoop down upon this numerically inferior Confederate army, while Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson's 18,000 men engaged Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's 11,000 men in the Shenandoah Valley, preventing them from reinforcing Beauregard.

The Union army was to drive the Confederates away and make a drive to Richmond. The war wasn't expected to last very long. Most people figured that the war would end a few months after it started. This is why the Union soldiers had to only enlist for 90-days at the beginning of the war. The commander of each inexperienced army planned an envelopement of the others left flank. Inadequate orders delayed the Confederate advance.

On July 21, by 2:00 A.M., McDowell had his 12,000-man flanking column marching down the Warrenton Pike from Centreville, where thy had been camped since July 18. His plan to attack Beauregard near Bull Run, a meandering stream to the east of Manassas, was sound, but it was too much for the raw Federals to execute, and he did not know that spies had reported his advance, giving Johnston the time he needed to reinforce Beauregard.

Shortly after 5:00 A.M., Union artillery north of Bull Run opened fire, while Union infantrymen feinted against the 8-mile long Confederate line. The flanking column forded the stream at Sudley Springs and deployed 3 hours behind schedule. Confederate signalmen had already detected the movement, and Confederate troops were rushing north to meet the threat.

The battle began in earnest in midmorning when Col. Nathan G. Evans' Confederates opposed the Union attack force. Evans urgently asked for reinforcements, which came piecemeal, slowly being drawn from the Confederate right, miles downstream. The troops of Evans, Brig. Gen. Barnard E. Bee and Col. Francis S. Bartow held until early noon against the disjointed Union attacks. Finally, the outnumbered Confederates cracked under the assaults, racing back across Young's Branch and the Warrenton Road. McDowell bolstered his attack force by funneling other units across Bull Run.

Beauregard and Johnston likewise sent reinforcements scrambling toward their crumbling left flank. One unit of these fresh troops was a brigade of 5 Virginia regiments commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson. Jackson took a defensive position on Henry Hill, down whose slope the remnants of Evans' and Bee's troops were streaming. Bee, trying to rally his shattered brigade, pointed to Jackson's line and shouted: "Look! There is Jackson standing like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!" Bee soon fell mortally wounded, but he had given Jackson his immortal nickname, "Stonewall".

In the meantime, the disorganized Federals regrouped. About 2:00 P.M., the Federals surged up the slope against Jackson's force. For the next 2 hours, the battle blazed up and down the hillside. Beauregard and Johnston arrived to prsonally direct the defense. Since, in the first months of the war, neither side had standard uniforms, the confusion and casualties compounded. Two Union batteries, mistaking a Confederate regiment for one of their own, were ravaged by a point-blank volley. This was considered the vital turning point of the battle, turning the momentum to the Confederates. Charges and countercharges swirled back and forth as the soldiers on both sides fought bravely. Throughout the battle, Confederate commanders kept bringing up reinforcements. Shortly before 4:00 P.M., with the last of Johnston's brigades now on the field, the Confederates ripped into McDowell's right flank, and rolled up the Union line.

The exhausted Federals at first retreated slowly across Bull Run, but a Confederate artillery shell hit a wagon on Cub Run Bridge, jamming the main avenue of retreat to Centreville. Some panicked, and the withdrawal turned into a route. Numerous spectators who had come from Washington to enjoy the war from a safe distance. The visiting elite were expecting an easy Union victory and had come to picnic and watch the battle.

When the Union army was driven back, the roads back to Washington, D.C. were blocked by the panicked civilians attempting to flee in their carriages and caught up in the unexpected rush. Further confusion ensued when an artillery shell fell on a carriage, blocking the main road north. A Union wagon overturned on a bridge spanning Bull Run and incited even more panic in McDowell's force.

Throughout the night, the frightened Union army filled the road back to Washington. The Confederates didn't pursue the Union army, which was later questioned by some Confederate authorities. Beauregard and Johnston decided not to press their advantage, since their combined army had been left highly disorganized, even in victory. Both armies were worn out by the battle and too inexperienced to make a controlled movement to follow the retreating Federals..

It was still very early in the war with the commanders on both sides learning as they went, as far as follow-up tactics. Meanwhile, the Confederates celebrated their decisive victory, now even more convinced that "One of them could whip 10 Yankees". The Union retreat became known as the "Great Skedaddle".

McDowell bore the brunt of the blame for the Union defeat at Bull Run and was soon replaced by Brig. Gen. George B. McClellan, who Lincoln named General-in-Chief of all the Union armies.

After this Union defeat, Lincoln realized that the war wouldn't be a quick war, but instead be a long and costly one.